Strategy pattern

Published:

Before we begin discussing the pattern itself, let’s create a simple model of a player that could be used in a game. The player needs to have the ability to attack and defend. The outcome of these actions will depend on the currently held weapon. Of course, this will be just a very simple example to focus our attention on the problem and solve it using the Strategy pattern (The code will be written in Java). Let’s start by creating a class representing the player:

public class Player {

String weapon;

public void atack() {

if(this.weapon == "Sword") {

System.out.println("Attacking with sword");

} else if (this.weapon == "Wand") {

System.out.println("Attacking with fireball";

}

}

public void defense() {

if(this.weapon == "Sword") {

System.out.println("Blocking attack with sword");

} else if (this.weapon == "Wand") {

System.out.println("Teleporting to safe place");

}

}

public void setWeapon(String weapon) {

this.weapon = weapon;

}

}

As you can see, the player has two methods for attacking and defending. Depending on the weapon assigned to the player, the corresponding action is performed. If we were creating a real game, we’d probably assign some basic weapon, like fists, in the constructor. For the sake of our example, we’ll skip this. However, note that we’ve implemented the setWeapon method, responsible for assigning the chosen tool to the player.

Remember, our weapons are just pretending to be real armaments. To illustrate the use of the pattern, we won’t need anything more. A simple indication of the type of attack we execute will be sufficient. There’s no need to overly complicate understanding a new pattern! 🙂

Now, we can proceed to test our player class.

public class Test {

public static void main (String[] args) {

Player player = new Player();

player.setWeapon("Sword");

System.out.println("Sword");

player.atack();

player.defense();

player.setWeapon("Wand");

System.out.println("\nWand");

player.atack();

player.defense();

}

}

As you can see, first, we create the player object, then assign a chosen weapon to him and execute an attack and defense. Next, we change the weapon and repeat the previous actions. The result?

Sword

Attacking with sword

Blocking attack with sword

Wand

Attacking with fireball

Teleporting to safe place

Process finished with exit code 0

As you can see, everything works! So, why do we need all these patterns? We’ve achieved the expected outcome with minimal effort. But what if you wanted to add more weapons? In games, we don’t usually have just two options. It’s often dozens, sometimes even thousands! And then what? Would the player class require hundreds of conditional statements to execute the right attack? It seems like it… Each new weapon would demand a new condition. This is at least impractical and highly unextensible. Moreover, what if we wanted to assign the already created weapon to an enemy controlled by the computer? We would have to duplicate our weapon code in his class.

I hope you can already feel how impractical this approach would be for extension. And here today’s discussed pattern comes to the rescue - the Strategy.

Strategy pattern in practice

Let’s start with its definition:

The Strategy pattern defines a family of algorithms, encapsulates each one as a separate class, and makes them entirely interchangeable. Applying this pattern allows changes in the implementation of processing algorithms to be entirely independent of the client utilizing them.

If it comes to me, these dry definitions don’t entirely help me understand how it’s supposed to work. Let’s try to apply this pattern in our example then.

Let’s start by creating the weapon interface:

public interface Weapon {

void atack();

void defense();

}

Our interface contains two methods responsible for the player’s attack and defense. Now that we have the interface, we can create classes for the weapons we used earlier.

public class Wand implements Weapon {

@Override

public void atack() {

System.out.println("Attacking with fireball");

}

@Override

public void defense() {

System.out.println("Teleporting to safe place");

}

}

public class Sword implements Weapon {

@Override

public void atack() {

System.out.println("Attacking with sword");

}

@Override

public void defense() {

System.out.println("Blocking attack with sword");

}

}

As you can see, each class representing a weapon implements the previously created interface. Alright, we’ve created the weapon classes. Now, we need to modify the player class.

public class Player {

Weapon weapon;

public void atack() {

this.weapon.atack();

}

public void defense() {

this.weapon.defense();

}

public void setWeapon(Weapon weapon) {

this.weapon = weapon;

}

}

Now, the variable “weapon” is no longer a String but a field corresponding to our weapon interface. Additionally, the attack and defense methods have changed. They now simply delegate the method calls to the weapon object. Do you see the difference? The player’s code has become more readable and straightforward. Plus, we’ve eliminated the conditional statements. As for setting the weapon, the changes are similar.

It’s time to test our player model after applying the pattern.

public class Test {

public static void main (String[] args) {

Player player = new Player();

player.setWeapon(new Sword());

System.out.println("Sword");

player.atack();

player.defense();

player.setWeapon(new Wand());

System.out.println("\nWand");

player.atack();

player.defense();

}

}

As you can see, we didn’t have to introduce many changes here either. Now, instead of assigning the weapon as a name by which the player class decides how the attack will work, we’re assigning an object of the appropriate weapon type. In this case, when setting the weapon, its new object is created, but we could also keep it stored in some variable. This would be useful if we wanted to enhance it in some way, etc. But let’s get back to our example.

Here’s what we’ll see in the console after running the code:

Sword

Attacking with sword

Blocking attack with sword

Wand

Attacking with fireball

Teleporting to safe place

Process finished with exit code 0

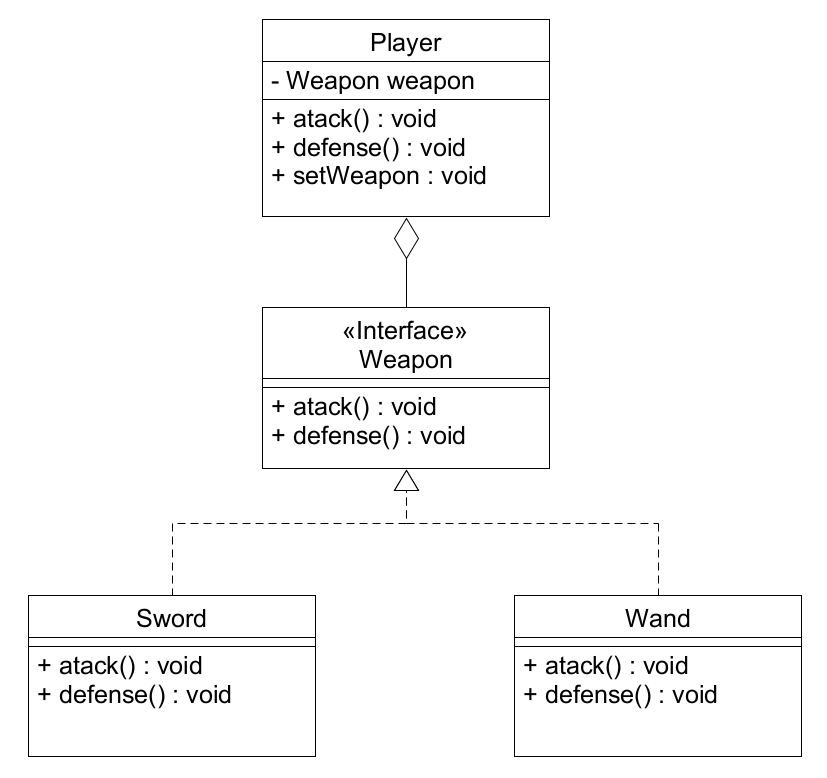

As you can see, the result is exactly the same as before applying the pattern. From an external perspective, nothing has changed, but if we were creating this type of game, implementing this pattern would open it up for extensions! We could easily add more weapons without modifying the player class. Now, it’s time for a diagram. This is how the Strategy pattern implemented in our code looks in a diagram:

Summary

Advantages of using the Strategy pattern

- Reduced number of conditional statements.

- Ability to choose implementations.

- Other object types can utilize previously created behaviors as they are no longer hidden in the parent class.

- Easy addition of new behaviors without modifying existing classes describing previous behaviors and without modifying classes that use them.

Disadvantages

- Increased communication cost between the client and the strategy (method invocation, data passing).

- Higher number of objects.

As you can see, in our case, applying the Strategy pattern had a very positive impact on both the code itself and its potential for future extensions. I hope that when creating your next game or application, you’ll recall this pattern at the right moment and use it if needed! 🙂