Decorator pattern

Published:

Today, we’ll discuss another design pattern! This time it’ll be the Decorator Pattern. But before we delve into it, let’s try to write a simple program (code written in Java).

Let’s assume you want to create a car dealership where you can order a car from a chosen brand in any possible configuration.

We’ll start by creating an abstract class representing a car.

public abstract class Car {

String description = "";

double price;

public String getDescription() {

return this.description;

}

public double getPrice() {

return this.price;

};

}

Our class has space for a car description where we’ll save the model’s name along with the chosen features, and also a field to hold the price of that particular model. Additionally, we have getters for both variables.

Now we can create our first specific model.

public class Golf extends Car {

public Golf() {

this.description = "Golf IV 1.9 TDI";

this.price = 9000;

}

}

As you can see, the code is very simple. We inherit from our abstract class and then, in the constructor, we set the description and price of a given model. To qualify our shop as a car showroom, it should offer the option to choose equipment for a particular car. So, let’s add a version of the Golf with heated seats and a version with air conditioning.

public class GolfWithHeatedSeats extends Car {

public GolfWithHeatedSeats() {

this.description = "Golf IV 1.9 TDI, heated seats";

this.price = 9900;

}

}

public class GolfWithAirConditioner extends Car{

public GolfWithAirConditioner() {

this.description = "Golf IV 1.9 TDI, air conditioner";

this.price = 9500;

}

}

Great! Our showroom already offers several versions of the reliable Golf. Let’s create several objects corresponding to them, then print out their parameters and prices.

public class CarDealership {

public static void main (String []args) {

System.out.println("Golf basic:");

Car car = new Golf();

System.out.println("Model: " + car.getDescription());

System.out.println("Price: " + car.getPrice() + "$");

System.out.println("\nGolf with heated seats:");

Car car1 = new GolfWithHeatedSeats();

System.out.println("Model: " + car1.getDescription());

System.out.println("Price: " + car1.getPrice() + "$");

System.out.println("\nGolf with air conditioner:");

Car car2 = new GolfWithAirConditioner();

System.out.println("Model: " + car2.getDescription());

System.out.println("Price: " + car2.getPrice() + "$");

}

}

After executing the above code, we should receive the following message.

Golf basic:

Model: Golf IV 1.9 TDI

Price: 9000.0$

Golf with heated seats:

Model: Golf IV 1.9 TDI, heated seats

Price: 9900.0$

Golf with air conditioner:

Model: Golf IV 1.9 TDI, air conditioner

Price: 9500.0$

Process finished with exit code 0

Great! Our showroom already has three versions of a particular car model. Of course, this is just the initial version, as ultimately we want to have a selection of at least several dozen models in various equipment configurations. Our program already has three classes corresponding to the three versions of the vehicle. But what if we wanted a Golf with both air conditioning and heated seats? We’d need to add another class. Notice that introducing a new equipment element significantly increases the number of classes. After all, we need to consider all the equipment combinations.

So far, for this particular model, we’ve had the option of:

- Heated seats

- Air conditioning

These two variations have forced us to create two additional classes! In total, we have three, including the basic version of the Golf, but we could use one more that includes both add-ons. Let’s assume we want to introduce sports brakes into the offer. How many classes do we need to cover all the variations? Let’s try to count it:

- Basic version

- Heated seats

- Heated seats and air conditioning

- Heated seats and sports brakes

- Heated seats, air conditioning, and sports brakes

- Air conditioning

- Air conditioning and sports brakes

- Sports brakes

As you can see, it’s getting quite complex. In this case, we’d actually need eight classes. And that’s still a small choice. In the future, we’d like to introduce additional features such as power windows, an alarm, parking sensors, a sporty intake system, tinted windows, a sports exhaust… Wow, the customization potential for the ordered model is truly impressive! Just like the number of classes we’d have to create to cover all these versions… It’s frightening to think about how much work it would require and how impractical it would be.

And what if we wanted to add another car model? We’d have to outline all the variations again, and then the number of classes in our project would double! Catastrophe… Fortunately, the solution we’re discussing today comes to our aid – the Decorator pattern.

Decorator pattern

Let’s start with the definition:

The Decorator pattern allows for dynamically assigning new behaviors to an object. Decorators provide flexibility similar to inheritance but offer significantly expanded functionality in return.

It’s another definition that might be tricky to visualize in practice. Let me show you how to implement it in our application.

public abstract class Car {

String description = "";

double price;

public String getDescription() {

return this.description;

}

public double getPrice() {

return this.price;

}

}

We’ll start with our abstract class representing a vehicle. As you can see, its code remains the same as before – we don’t need to make any modifications to it. However, we’ll need an entirely new class specific to our pattern. It will be an abstract decorating class, which in this case, we’ll name CarDecorator.

public abstract class CarDecorator extends Car {

Car car;

public abstract String getDescription();

public abstract double getPrice();

}

As you can see, it inherits from our Car class to ensure type compatibility. It has a variable of type Car and overrides both getters, turning them into abstract methods – these will require overriding in classes that inherit from it. The vehicle model remains unchanged.

public class Golf extends Car {

public Golf() {

this.description = "Golf IV 1.9 TDI";

this.price = 9000;

}

}

Now, it’s time for something interesting. We’ll create a class that will allow us to decorate a car with air conditioning!

public class AirConditioner extends CarDecorator {

public AirConditioner(Car car) {

this.car = car;

this.description = ", air conditioner";

this.price = 500;

}

@Override

public double getPrice() {

return this.car.getPrice() + this.price;

}

@Override

public String getDescription() {

return this.car.getDescription() + this.description;

}

}

As you can see, this class inherits from the abstract class CarDecorator. An important aspect here is that in the constructor, we take a parameter of type Car and assign it to the ‘car’ field declared in the parent class. Similar to setting the car model, we also set the description and price of the specific component. Here, we override the abstract methods as well. Notice that they return the price and description of the Car object passed to them, adding the data set in the constructor. Similarly, we’ll create a class responsible for heated seats.

public class HeatedSeats extends CarDecorator {

public HeatedSeats(Car car) {

this.car = car;

this.description = ", heated seats";

this.price = 900;

}

@Override

public double getPrice() {

return this.car.getPrice() + price;

}

@Override

public String getDescription() {

return this.car.getDescription() + description;

}

}

As you can see, adding another decorating object is very simple. We have everything we need to test our enhanced car showroom! Let’s create an object for a Golf equipped as before with air conditioning and heated seats. Additionally, we’ll create a Mustang similarly equipped to the Golf but with the addition of sports brakes and LED lights. You should already be able to write the code for the Mustang class and the additional equipment yourself without any problems.

public class CarDealership {

public static void main (String []args) {

System.out.println("Golf:");

Car car = new Golf();

car = new AirConditioner(car);

car = new HeatedSeats(car);

System.out.println("Model: " + car.getDescription());

System.out.println("Price: " + car.getPrice() + "$");

System.out.println("\nMustang:");

Car car2 = new Mustang();

car2 = new AirConditioner(car2);

car2 = new HeatedSeats(car2);

car2 = new SportBrakes(car2);

car2 = new LedLights(car2);

System.out.println("Model: " + car2.getDescription());

System.out.println("Price: " + car2.getPrice() + "$");

}

}

The code responsible for testing our showroom and creating new cars looks a bit different this time. We’re not creating an instance of a class corresponding to the model with selected equipment. Instead, we create a base object, which is the car model, and decorate it (wrap it) with the appropriate equipment elements. When you run the above code, you’ll receive the following message:

Golf:

Model: Golf IV 1.9 TDI, air conditioner, heated seats

Price: 10400.0$

Mustang:

Model: Mustang 5.0L, air conditioner, heated seats, sport brakes, led lights

Price: 33900.0$

Process finished with exit code 0

As you can see, our code works brilliantly! Now, we don’t need to create specific car variants. It’s enough to add a decorator corresponding to the chosen equipment element, and we can wrap it around different car models. Additionally, we don’t need to manually calculate prices or write descriptions for each car variant every time. Each equipment class has its price and description, and the program automatically computes these values when using the getters.

You should already see how effectively we’ve reduced the number of necessary classes and how much we’ve expanded our showroom’s capabilities. Admittedly, our code assumes that a specific equipment element costs the same regardless of the car it’s added to. That’s far from reality, but adding the ability to set prices is no problem. Take a look at the following code:

public HeatedSeats(Car car, double price) {

this.car = car;

this.description = ", heated seats";

this.price = price;

}

Simply modify the constructor of the chosen decorator and set the price during decoration. Easy, right? This way, we can add and define further attributes for decorators, but that’s already beyond the scope of this article.

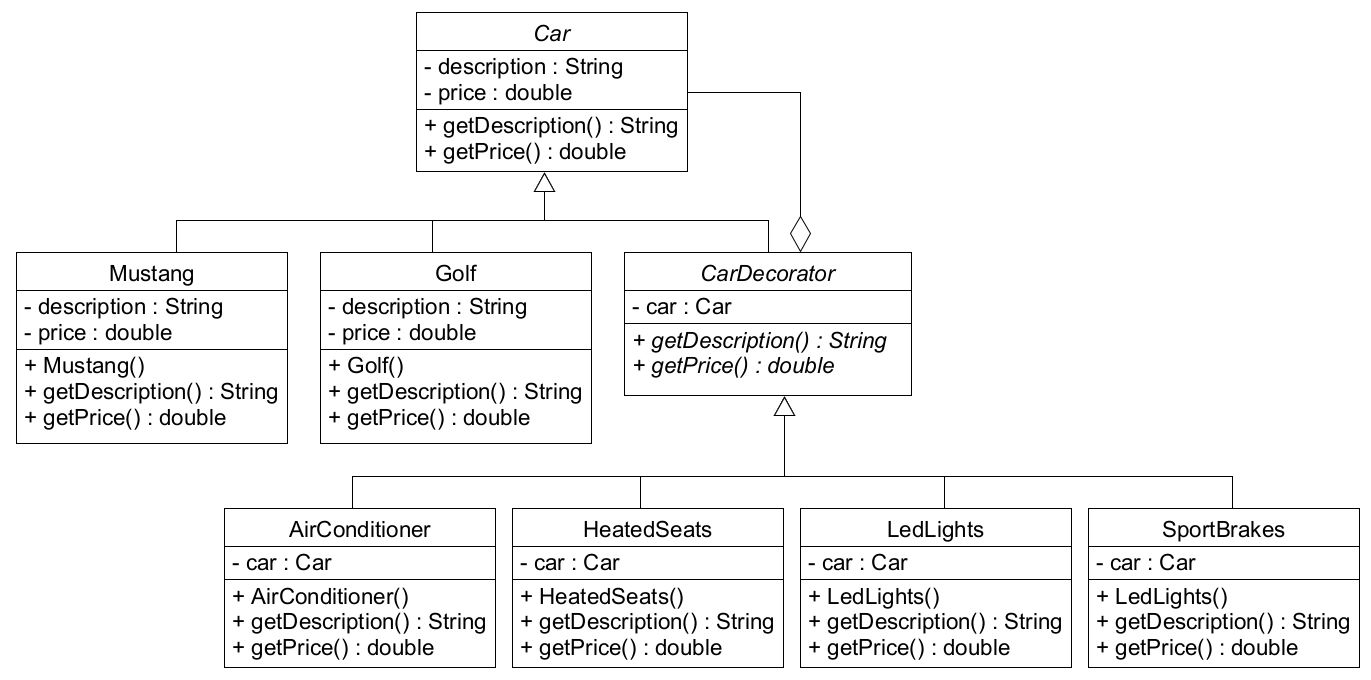

Finally, take a look at how the class diagram of our program looks:

Summary

I hope this example shed some light on how the Decorator pattern works and might help you implement it in your project if needed. With this pattern, we can create new functionalities not by inheriting from a parent class but by composing individual objects.

Notice that by using this pattern, we have the ability to extend behaviors of a selected class without modifying its code. Moreover, we can wrap our component (in this case, the car model) any number of times, even during runtime!

It’s also worth noting that decorators are typically entirely transparent to the clients of the component. From their perspective, objects look and behave exactly the same as non-wrapped ones. They are handled in the same way. Of course, as long as the client’s functioning isn’t dependent on the actual implementation of the component.

Certainly, in similar scenarios, simple inheritance can be used as a way to extend class functionality, but it might not always be the best approach for creating flexible, extensible projects.

The Decorator pattern discussed today isn’t without its flaws. Depending on the project, it can lead to the creation of many small objects and overusing decorators may increase code complexity.